We hit the wall at 200 tools.

That’s when everything broke. The model would try to send a Slack message and call the Gmail API instead. Or it would freeze, paralyzed by choice, and refuse to call anything at all. Response times ballooned. Costs spiked. The context window was so bloated with tool schemas that the model barely had room to think.

OpenAI caps tools at around 128 per request. We weren’t even close to that number technically, but functionally? The model was already drowning.

How do you support thousands of tools without choking the LLM?

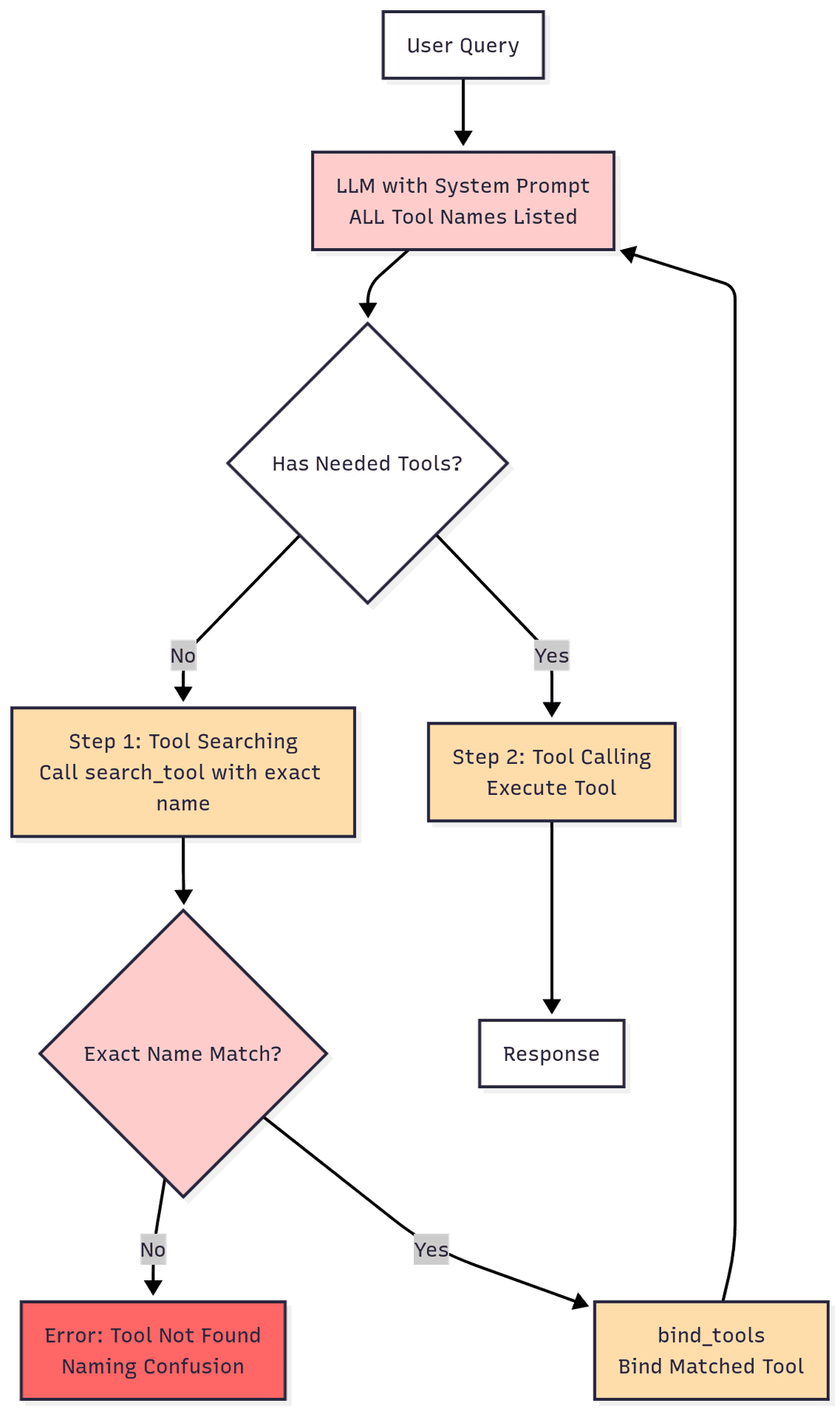

The Naive Approach: Manual Tool Search

Our first attempt was tool search. We’d list every available tool name in the system prompt, then give the model a search_tool function. When it needed something, it would call search_tool("gmail send email"), we’d look it up, bind it dynamically, and return it.

Clever, right?

It failed spectacularly.

LLMs don’t follow strict naming conventions when you have hundreds of options. They guess. They paraphrase. They hallucinate tool names that sound plausible but don’t exist. And even when they got it right, the system prompt listing all those tools still consumed the context window — we’d just moved the problem from tool schemas to tool names.

We tried it anyway. It worked for 20 tools. At 50, it started breaking. At 200, it was unusable.

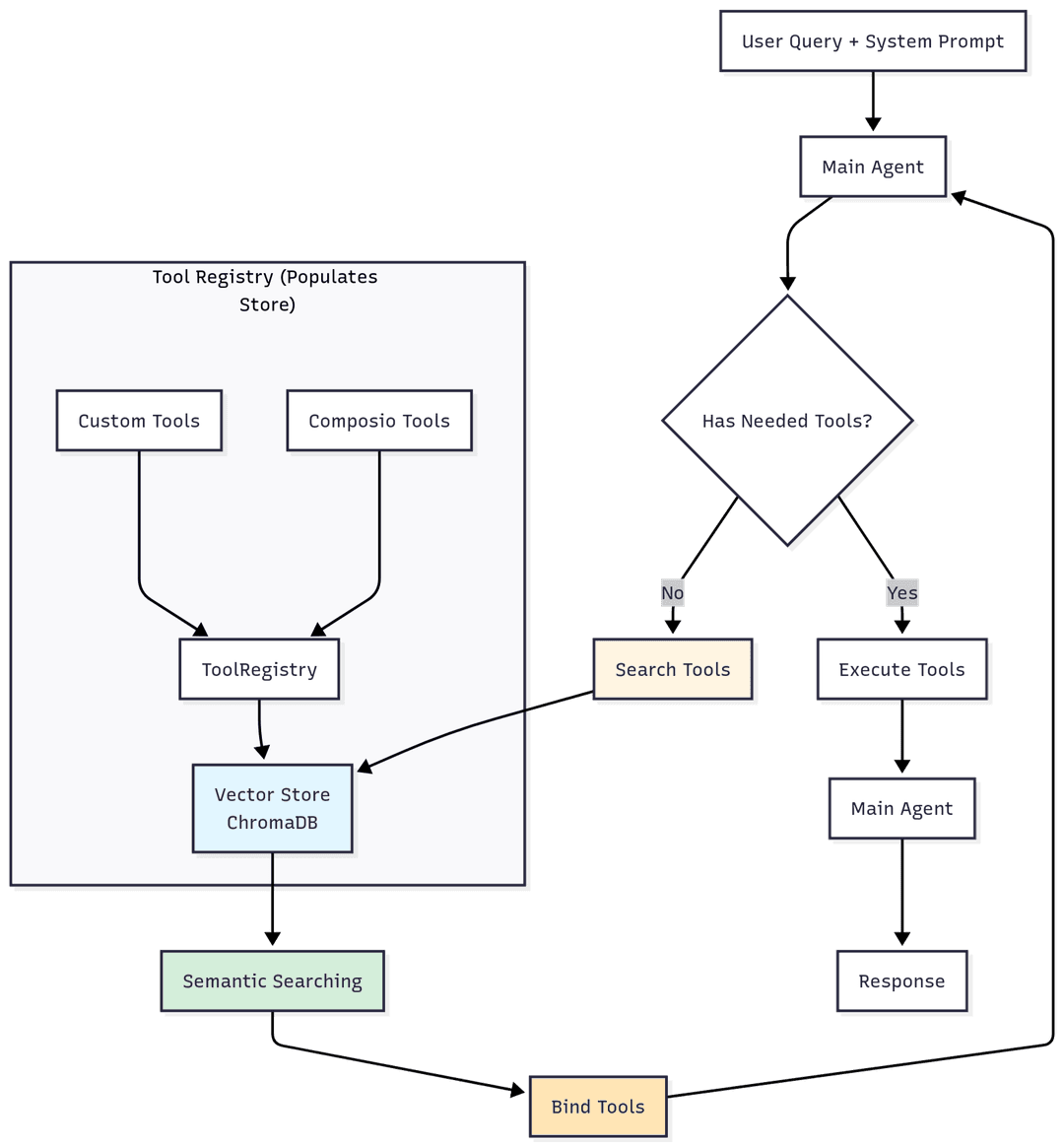

The Breakthrough: Semantic Tool Retrieval

Then we found LangGraph Big Tools — a small package that flipped the entire problem on its head.

Instead of forcing the model to remember exact tool names, it turns tool discovery into semantic search. Here’s how:

- Every tool (name + description) gets embedded into a vector store (we use ChromaDB)

- When the model needs a tool, it writes a natural language query: “I need to fetch the last 10 emails from Gmail”

- A

retrieve_toolsfunction searches the vector store and returns the most relevant matches - Those tools get dynamically bound to the model at runtime

The difference was immediate. Context window usage dropped substantially. The model stopped hallucinating tool calls. We went from supporting dozens of tools reliably to thousands without degradation.

And because retrieval is fast, latency actually improved compared to loading everything upfront.

Building the ToolRegistry

Solving discovery wasn’t enough — we needed a way to manage real integrations at scale. That’s where the ToolRegistry came in.

It handles:

- Fetching tools from Composio (pre-built integrations for Slack, Gmail, GitHub, etc.) and custom sources

- Embedding everything into ChromaDB for semantic retrieval

- Tracking OAuth tokens, user IDs, and authentication state

- Dynamic binding at runtime

The registry is the single source of truth for what tools exist and how to access them. When the executor needs a tool, it queries the registry. When a user connects a new integration, the registry indexes it immediately.

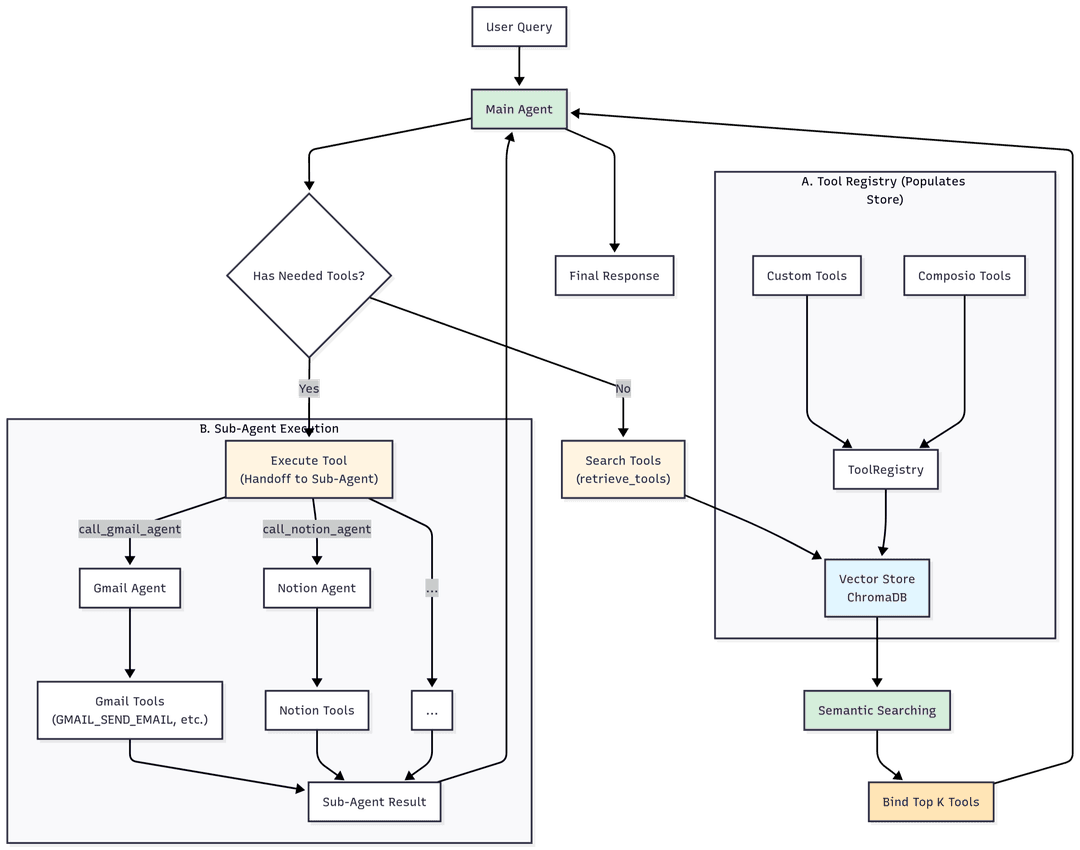

The Three-Layer Architecture

Discovery and the ToolRegistry solved tool management. But who actually uses these tools?

Most AI frameworks throw everything into one agent — conversation, tool selection, memory, execution. It works for demos. It collapses in production.

The problem: your model is simultaneously trying to sound human, route between 500+ tools, remember preferences, and execute API calls. That’s too many jobs for one context window.

Gaia runs a three-layer hierarchy where each layer does one thing well.

1. The Communications Agent

This is what you talk to. And it exists as its own layer for a reason.

Most AI assistants feel robotic because their personality is an afterthought. The model is busy thinking about tool schemas and API parameters while trying to sound conversational. The result is that sterile “I’d be happy to help you with that!” energy.

We solved this by giving conversation its own agent. The comms agent’s entire context window is dedicated to understanding you — your tone, mood, history, and intent. It doesn’t waste a single token on tool schemas.

It has exactly three tools:

call_executor— delegates action tasksadd_memory— stores something for latersearch_memory— recalls stored info

That’s it. No Gmail, no GitHub, no calendar tools.

Why this works: With only 3 tool schemas in context, the comms agent has massive headroom for what it’s actually good at — understanding context and communicating naturally. It reads your tone. If you’re stressed, it’s direct. If you’re casual, it matches. It mirrors your vocabulary, pacing, and energy.

When you say “hey send an email to John about the meeting,” the comms agent doesn’t try to figure out SMTP. It acknowledges like a person would — “on it” or “pulling that up” — then calls call_executor with a detailed task description.

When results come back, the comms agent rewrites the raw output in your tone. The executor’s clinical “Email drafted to john@company.com, subject: Meeting Update, status: awaiting approval” becomes “drafted the email to john — check it out and lmk if it looks good.”

The key insight: Separating conversation from execution makes both layers better. The comms agent is better at conversation because it’s not distracted by tools. The executor is better at execution because it’s not trying to be friendly.

2. The Executor Agent

The executor receives tasks from the comms agent and figures out how to complete them.

It has:

retrieve_tools— semantic search across the entire ToolRegistryhandoff— delegates to specialized subagents- Access to the full ToolRegistry through discovery

Why a separate executor? Because orchestration is a fundamentally different skill than conversation. The executor doesn’t waste tokens on personality or tone matching. Its entire context is optimized for one question: what’s the fastest path to completing this task?

Here’s the executor’s logic:

Task: “Send an email to John about the meeting being moved to Friday”

Step 1: This is an email task → Gmail has a subagent

Step 2:handoff(subagent_id="gmail", task="Send an email to John informing him the meeting is moved to Friday.")

For well-known integrations (Gmail, Calendar, GitHub, Slack), the executor skips discovery and hands off directly — it already knows which subagent handles what. This saves a round-trip and cuts latency.

For newer or less common tools:

Task: “Add this to my Airtable”

Step 1:retrieve_tools(query="airtable database")

Step 2: Finds “subagent:airtable” in results

Step 3:handoff(subagent_id="airtable", task="Add the item to Airtable")

The executor also handles multi-step orchestration. If a task requires multiple integrations — “check my calendar for tomorrow, then email the team with a summary” — the executor coordinates handoffs sequentially, passing context between subagents.

The executor never chats. It never explains. It executes, returns results, and occasionally suggests turning repetitive tasks into automated workflows.

3. Provider Subagents

Each integration gets its own dedicated agent. Gmail has one. GitHub has one. Notion has one.

Why not just call tools directly from the executor? Because platforms are complicated. Sending an email isn’t just “call the send endpoint.” It’s: resolve the recipient from a name, check for existing threads, create a draft first (users hate accidental sends), handle attachments, respect signature preferences. A generic agent with 500 tools would get half of this wrong.

Each subagent:

- Has its own scoped tool registry — it only sees its own tools, so there’s zero chance of calling the wrong API

- Gets a domain-specific system prompt — the Gmail subagent knows about draft-first workflows and recipient resolution. The Twitter subagent knows thread creation rules. The Notion subagent knows to search before creating to avoid duplicates.

- Has its own checkpointer — conversation memory scoped to that integration, so multi-turn tasks work naturally (“now update that draft” works because the subagent remembers the

draft_id) - Learns skills over time — procedural knowledge specific to this user and integration

- Accesses user memories — preferences, contacts, IDs from past interactions

The scoping is what makes this work. Each subagent’s context contains only its own tools and expertise — no noise. The model operates in a focused environment where every token is relevant.

When the executor calls handoff(subagent_id="gmail", task="..."):

- The system resolves the subagent ID to the right integration config

- If the subagent hasn’t been loaded yet, it’s lazy-loaded — tools fetched, registered, and indexed on the fly

- A fresh execution context is built: domain-specific prompt, user context (timezone, memories, learned skills), and the task description

- The subagent’s graph streams execution — tool calls, progress, and results flow back through the executor to the comms agent in real time

The Layers at a Glance

| Layer | Purpose | Tool Count | Context Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comms Agent | Conversation + delegation | 3 | Understanding the user, responding naturally |

| Executor | Orchestration + routing | Dynamic (via retrieval) | Figuring out what to do and who does it |

| Subagent | Domain execution | 10-50 (scoped) | Executing within one integration with deep expertise |

How Custom Integrations Work

Beyond the built-in integrations, users can connect custom MCP servers — any tool that speaks the Model Context Protocol. This is what makes Gaia extensible beyond the integrations we’ve built ourselves.

When a user adds a custom MCP integration:

- Gaia connects to the MCP server and fetches all available tools

- Those tools get registered under a user-specific namespace (so your tools don’t collide with another user’s)

- They’re indexed in ChromaDB so the executor can discover them semantically — the user doesn’t need to remember tool names

- A new subagent is created on-the-fly for that integration, with its own scoped context

The subagent for a custom MCP gets a universal prompt — since we don’t have domain-specific knowledge about arbitrary integrations, the system focuses on general execution principles: try hard, retry on failure, verify assumptions, exhaust alternatives before reporting impossibility.

Why this matters: Any MCP-compatible tool server becomes a first-class Gaia integration with zero custom code. Private internal tools, niche SaaS platforms, self-hosted services — they all get the same semantic discovery, scoped execution, and memory learning that built-in integrations have.

Memory and Learning

Subagents aren’t stateless. Every subagent has a memory learning hook that runs after each execution. It extracts two kinds of knowledge:

- Skills — procedural knowledge, stored per-agent. “When creating a GitHub issue in this repo, always use the ‘bug’ label and assign to the triage team.” The Gmail subagent accumulates Gmail-specific patterns. The Twitter subagent accumulates Twitter-specific patterns. Skills are scoped, so one integration’s lessons never contaminate another.

- User memories — preferences, IDs, contacts, stored per-user. “John’s email is john@company.com. The user prefers drafts before sending. Their primary calendar is ‘Work’.”

Next time a subagent runs, it searches both skill memory and user memory for anything relevant to the current task. This means the system gets tangibly better over time. The first time you ask to email John, it needs to search your contacts. The tenth time, it already knows his address. The first time you create a GitHub issue, it uses the default template. After a few interactions, it knows your repo’s conventions.

This is the difference between a tool and an assistant that actually knows how you work.

The Full Flow

Here’s what actually happens when you send “email John that the meeting moved to Friday”:

-

Your message hits the comms agent. It recognizes this needs action, sends a casual acknowledgment, and calls

call_executorwith the full task description. -

The executor receives the task. It recognizes Gmail as a known provider and calls

handoff(subagent_id="gmail", task="..."). -

The handoff tool resolves the subagent. If the Gmail subagent isn’t loaded, it lazy-loads — tools fetched, registered, indexed, graph created with its own checkpointer.

-

The Gmail subagent builds its context. Domain-specific prompt, relevant user memories (maybe it already knows John’s email), learned skills — all packed into the initial state.

-

The Gmail subagent executes. It discovers the right email tools in its scoped registry, resolves John’s contact, creates a draft, and presents it for review.

-

Results stream back up. Tool calls, progress, and the final response flow from subagent → executor → comms agent → your screen — rewritten in your tone before you see it.

What’s Next: Self-Learning and Speed

The architecture works. Now we’re making it fast.

The current system is built for correctness — every task routes through the right subagent, executes with domain expertise, and returns reliable results. But there’s overhead. When you ask Gaia to email your team every Friday with a project update, it goes through the full routing process every time: comms → executor → handoff → subagent → tool discovery → execution.

We’re building a self-learning skills layer that changes this.

Here’s the idea: the first time you run a multi-step workflow, the system executes it normally and records the exact sequence. The second time you ask for the same pattern, the system recognizes it and shortcuts the entire flow — no routing, no discovery, just execution. The LLM remembers procedural patterns and replays them directly.

This applies to everything from simple recurring tasks (“email John the weekly update”) to complex multi-integration workflows (“pull yesterday’s Linear issues, summarize them, and post to Slack #engineering”). If it’s happened once, the system knows how to repeat it instantly.

The result: Significant latency reductions for repeated patterns. For one-off tasks, the architecture stays the same — reliable, well-routed, and correct. For recurring workflows, the system gets dramatically faster over time.

We’re also tightening streaming across the layers. Right now, tool calls and results flow back through each layer sequentially. We’re working on partial result streaming so you see progress in real time, not just the final output.

Try It Yourself

If you want to see the code behind all of this, Gaia is open source.